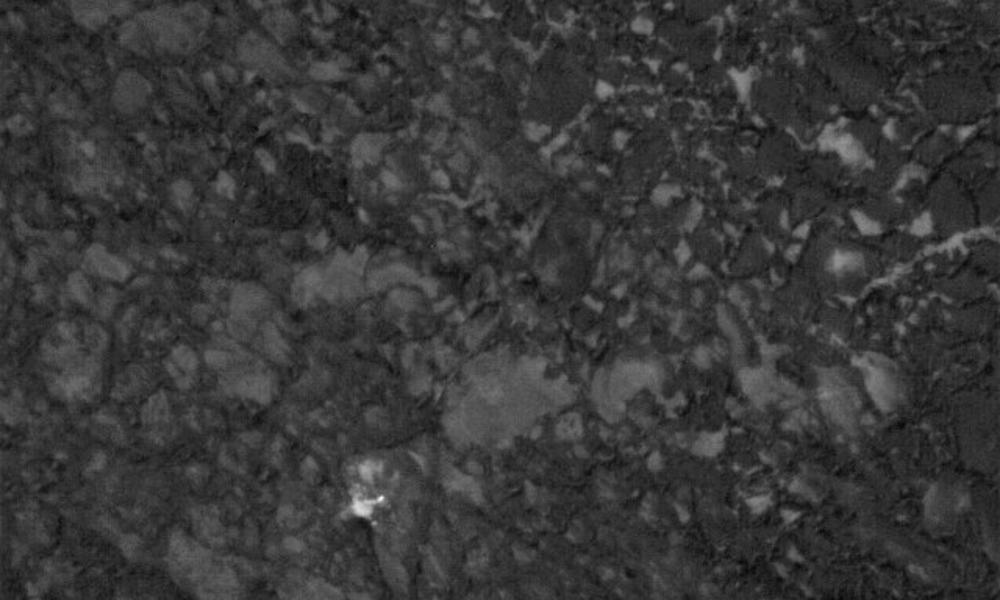

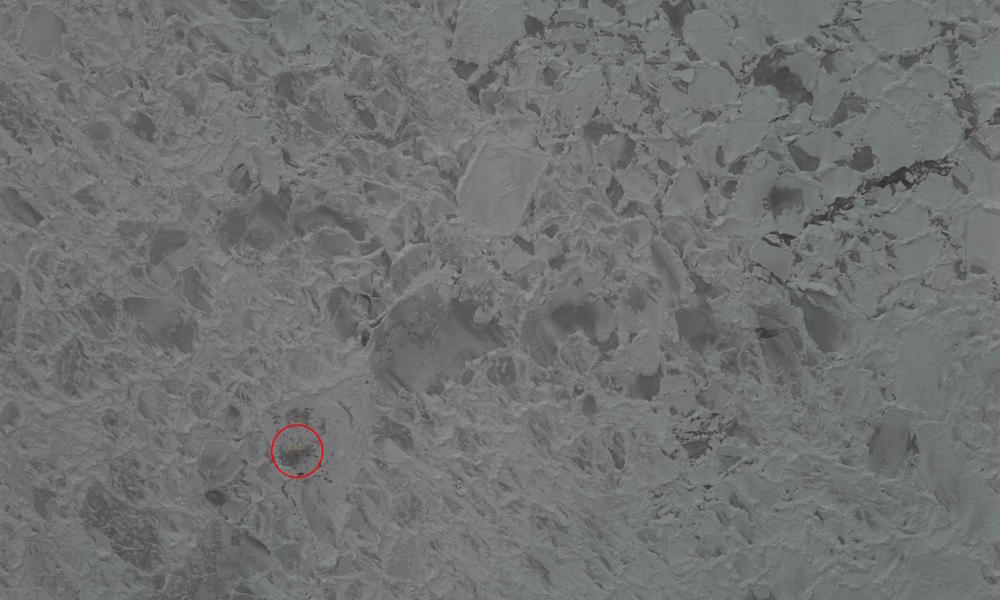

Can you see the polar bear? Left: High-resolution aerial photograph. Right: Thermal image. (Can’t see this image? Open in a new tab.) Photos: NOAA Fisheries

This month, scientists from the USA and Russia are working together to estimate the size of a never-before surveyed subpopulation of polar bears, using infrared thermal camera technology attached to an airplane. Sound like something out of a James Bond movie? Actually, thermal imaging has been used in wildlife studies for quite some time to detect mammals such as squirrels, deer and kangaroos, as well as birds like woodpeckers and ducks. But this survey will be the first to use the technology on polar bears at such a large scale.

The survey, carried out by NOAA Fisheries and Russian scientists from the Russian State Research and Design Institute for the Fishing Fleet, is taking place in the Chukchi Sea, which lies between the US State of Alaska and Eastern Russia and spans almost 600,000 km2 in area (almost the size of Australia). The Chukchi Sea is home to one of 19 subpopulations of polar bears in the Arctic, as well as several species of seal, two of which will also be the focus of this survey.

See more: Collaborating to count Arctic seals and polar bears

The survey technique uses a combination of high-resolution colour photographs and infrared images to detect bearded seals, ringed seals and polar bears from an aircraft flying at a height of around 300m. Being warm-blooded in the cold Arctic environment, the heat signature of each individual bear and seal can be seen by the infrared camera as a white “blob” against a black background. The high-resolution colour photographs will then allow scientists to zoom in and identify each “blob” as a seal or a bear.

Polar bears can indeed be detected with a thermal camera. Here, a bright spot indicates an object much warmer than the surface of the ice.

© NOAA Fisheries

A corresponding color photo shows the same scene. Could you find the polar bear without the help of the red circle?

© NOAA Fisheries

Now, a close-up of that photograph reveals it is truly a polar bear on the ice.

© NOAA Fisheries

Once proven successful, this new method will be added to the toolbox of techniques used by scientists to monitor population trends over time. Why do we need this information? The biggest threat to polar bears globally is climate change. We need to understand how bears are responding to a warming Arctic so their populations can be properly managed. Understanding whether populations are declining, stable or increasing in size helps with this. Less summer sea ice as a result of climate change has already been shown to affect body weight, number of cubs born, and even survival of young polar bears in some areas of the Arctic.

Many of us think of the Arctic as a remote, pristine place that is shielded from the negative effects of the southern world. For most of us, polar bears are not our neighbours, but the activities taking place in our own backyards are undoubtedly causing their Arctic home to feel the heat. The Chukchi Sea polar bears are no exception. The Chukchi Sea is influenced by the warmer waters of the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, and researchers have predicted that some of the greatest losses of polar bear habitat will occur here by the 21st century. This survey is therefore an important piece of the conservation puzzle for Russia and the USA, who in 2007 formed a bilateral Agreement to conserve and manage this shared polar bear subpopulation.

While monitoring trends in polar bear populations is important for understanding their response to a changing Arctic, this alone will not be enough to ensure the future of this iconic species. Polar bears occur in five countries across the world – Russia, USA, Canada, Norway and Greenland (Denmark). These countries have agreed to work together to secure the long-term persistence of polar bears in the wild. In addition to climate change, they will address other threats including mineral and energy resources development, shipping, disease and defence killing of polar bears. This will be achieved through a 10-year Circumpolar Action Plan for Polar bears, with the first milestones of this agreement due to be evaluated in 2017.